The air is thick with the scent of rain on dry earth, and suddenly, you are eight years old again, standing in your grandmother’s garden after a summer storm. This visceral, time-traveling power of smell is one of humanity’s most universal yet mysterious experiences. Unlike the other senses, smell bypasses the thalamus, the brain’s typical relay station, and journeys directly to the primary olfactory cortex, a gateway intimately wired into the brain’s emotional and memory centers—the amygdala and hippocampus. This unique neural architecture suggests that our sense of smell, particularly retronasal olfaction—the perception of odors from food and drink inside the mouth—is not merely a sensory input but a profound architect of our emotional past and present.

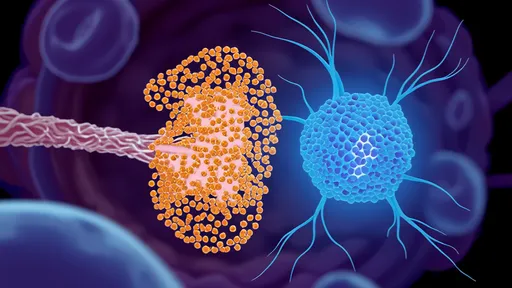

Retronasal olfaction occurs when volatile compounds from consumed food or drink travel up the back of the nasal passage to the olfactory epithelium. This is distinct from orthonasal olfaction, the act of sniffing an external scent. While both pathways culminate in scent perception, their neurological and psychological impacts differ significantly. The retronasal route is inherently linked to ingestion and satiety, weaving smell directly into the experiences of flavor, nourishment, and ultimately, survival. This intimate connection to a fundamental life process hints at why smells perceived this way can become so powerfully tethered to our most foundational memories and feelings.

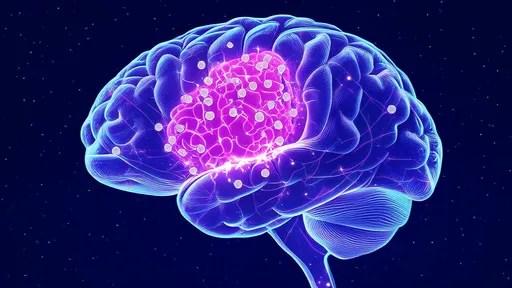

The neural link between retronasal smell and emotional memory is a fascinating dance of chemistry and electricity. When odor molecules bind to receptors in the nose, they trigger signals that race along the olfactory nerve. These signals do not first travel to the thalamus for processing, as visual or auditory information does. Instead, they make a beeline for the piriform cortex, the main part of the primary olfactory cortex. From there, connections are immediate and robust to the amygdala, which processes emotion, and the hippocampus, which is essential for forming new memories. This direct line gives smell an unparalleled ability to evoke emotional memories with an intensity and vividness that sights or sounds often cannot match.

This process is not a simple one-to-one relay. Neuroimaging studies using fMRI have shown that retronasal odors activate a more extensive and nuanced network than orthonasal odors. The act of tasting a familiar food, and thus experiencing its smell retronasally, can trigger robust activity in the hippocampus and the amygdala, alongside regions associated with reward processing like the orbitofrontal cortex. This suggests a complex integration where the brain is not just identifying a smell but is actively retrieving the emotional context and autobiographical memory associated with it. It is a full-brain recollection, pulling from the sensory, the emotional, and the experiential simultaneously.

The strength of these olfactory-emotional connections is often forged during childhood. Early life is a period of rapid brain development and intense first experiences with food and flavor. The smell of a specific brand of cookies, the unique aroma of a family stew, or the scent of a particular fruit—all perceived retronasally during meals—become encoded into memory alongside the emotional climate of those moments: comfort, joy, security, or celebration. Because the olfactory system is so mature at birth, these early associations are laid down with incredible durability, creating a subconscious library of scent-emotion pairs that can be triggered for a lifetime.

This mechanism has profound implications that extend far beyond nostalgia. In the realm of mental health, understanding this link offers new avenues for therapy. For individuals with PTSD, certain smells can trigger debilitating flashbacks. Conversely, the deliberate use of positive, comforting retronasal smells (like a familiar, calming tea or food) could be integrated into therapeutic practices to help anchor patients in the present or build new, positive associations. It represents a non-invasive tool to access and potentially recalibrate the emotional brain.

In the world of marketing and product design, particularly in the food and beverage industry, this science is already being applied. Food scientists and flavorists are keenly aware that a product’s success is not just about taste on the tongue but about the entire retronasal smell experience and the emotions it evokes. Brands strive to create flavors that trigger feelings of nostalgia, comfort, or luxury, understanding that a positive emotional response is a powerful driver of consumer loyalty. The goal is to design a taste signature that doesn’t just satiate hunger but also feeds an emotional need.

Perhaps one of the most poignant applications is in the context of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's. The olfactory system is often one of the first pathways to be affected by the disease, which explains why loss of smell is an early symptom. As the illness progresses, patients often lose recent memories but can retain vivid recollections from their distant past. The use of potent, familiar retronasal smells from their childhood—the aroma of a favorite long-forgotten pastry or drink—has been shown to sometimes elicit clear, emotional responses and memory retrieval, offering a rare and valuable window for connection and comfort when other communicative avenues have closed.

The study of retronasal olfaction and its emotional links is also pushing the boundaries of artificial intelligence and robotics. For AI to interact with humans in a truly intuitive and empathetic way, it may need to understand context and emotion, not just data. Research into how the brain codes these smell memories is providing a biological blueprint for creating more sophisticated neural networks. Engineers are interested in developing artificial olfactory sensors that can not only detect chemicals but also interpret their potential emotional valence, which could revolutionize fields from environmental monitoring to personalized healthcare.

Ultimately, the science of retronasal olfaction reveals that our sense of smell is far more than a detector of environmental cues or a simple component of taste. It is a deep, hardwired conduit to our most personal histories. The flavor of a meal is a conversation between our palate and our past, a dialogue mediated by a sophisticated neural network that binds chemical molecules to the very essence of human experience—emotion and memory. This hidden sense, operating quietly from the back of our mouth, is a constant, unconscious curator of the story of who we are.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025