In the burgeoning field of sustainable nutrition, a quiet revolution is underway, one that seeks to transform the very essence of what we consider palatable. The concept of utilizing insects as a primary protein source is no longer confined to the realms of survivalist manuals or niche culinary adventures. It has entered the mainstream discourse on food security, propelled by an urgent need for environmentally responsible alternatives to traditional livestock. However, the path to widespread adoption is fraught with a significant, deeply ingrained barrier: the human palate. The challenge is not merely to introduce insects as food but to fundamentally re-engineer both their flavor profile and physical form, making them not just acceptable, but desirable.

The journey begins with the most immediate sensory encounter: taste. For many, the idea of consuming crickets, mealworms, or locusts is immediately vetoed by an anticipated unpleasant flavor, often described as earthy, musty, or simply "bug-like." This is where the sophisticated science of flavor masking comes into play. It is a discipline that moves far beyond simply covering up an undesirable taste with a strong sauce. Modern food scientists are delving into the molecular composition of insect-derived flavors to understand their core components. These off-putting notes are often the result of specific volatile organic compounds and lipids that oxidize rapidly after processing.

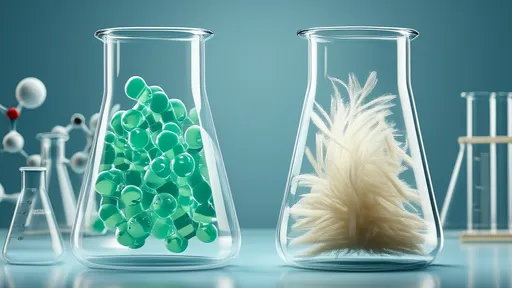

Advanced techniques are being employed to neutralize these compounds at their source. One prominent method involves blanching or quick-steaming insects immediately post-harvest. This rapid application of heat deactivates enzymes that are responsible for the development of bitter and rancid flavors during storage. Furthermore, lipid extraction processes are being refined to remove the fats that are most prone to oxidation, thereby significantly extending shelf life and improving initial taste. The goal is to create a neutral, almost bland insect base ingredient—a blank canvas upon which a myriad of flavors can be artfully painted.

Once a neutral base is achieved, the true artistry of flavor creation begins. This is not about masking but about harmonizing and integrating. Food technologists are experimenting with complex flavor systems derived from spices, herbs, umami-rich ingredients like mushrooms and tomatoes, and even through fermentation processes. The application of Maillard reaction products—those complex, savory flavors created when proteins and sugars are heated—is particularly effective. By coating insect powder or paste with specific amino acids and reducing sugars before a controlled heating process, scientists can generate rich, meaty, roasted, or nutty flavors that are highly appealing and completely overshadow any residual "insect" taste.

Yet, conquering the tongue is only half the battle. The human brain, and indeed the eye, are equally powerful gatekeepers. The sight of a whole insect, with its recognizable legs, antennae, and segmented body, triggers a deep-seated psychological rejection in many cultures. This is why morphological reconstruction is the second, equally critical pillar of insect-based food development. The objective is to break down the insect entirely and reassemble it into something familiar and non-threatening.

The most common and successful approach is milling dried insects into a fine powder, often referred to as cricket flour or mealworm powder. This ingredient can then be seamlessly incorporated into a vast array of established food products. We are already seeing its successful integration into protein bars, pasta, crackers, baking mixes, and snack chips. In these forms, the insect component is invisible, its nutritional benefits delivered without any visual cues that might cause aversion. The consumer enjoys a familiar texture and appearance, receiving the protein boost as a hidden benefit.

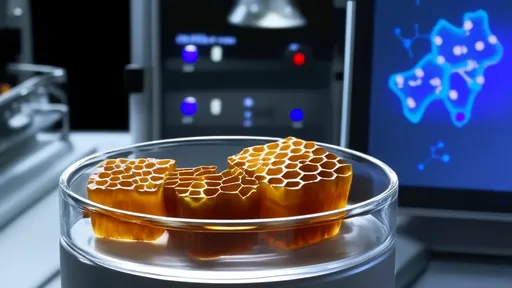

However, the frontier of morphological reconstruction is pushing into far more advanced territory. Using high-tech processes like extrusion and 3D food printing, researchers are beginning to create entirely novel structures. Extrusion technology, which uses heat, pressure, and shear force to reshape food materials, can transform insect biomass into textured protein pieces that mimic the fibrous quality of chicken, beef, or pork. These can be used in applications like vegetarian burgers, nuggets, or taco fillings, providing a sustainable and complete protein source that aligns with familiar meat-eating experiences.

Even more futuristic is the application of 3D food printing. This technology allows for unprecedented precision in structuring food layer by layer. Imagine a printer that can deposit precisely measured amounts of insect protein powder, binders, and flavorings to construct a gourmet snack with a complex, delicate architecture that would be impossible to achieve by hand. It could create visually stunning and delicious products that are first judged on their culinary merit, with their innovative origin becoming a point of intrigue rather than a barrier.

The synergy between flavor masking and morphological reconstruction is where the most promising products are emerging. A company might use defatted and de-flavored cricket powder, imbue it with smoky barbecue flavor through Maillard reaction techniques, and then use extrusion to form it into a jerky-like strip. The result is a product that tastes, chews, and looks like a conventional beef jerky but is produced with a fraction of the environmental footprint. This holistic approach addresses the consumer on multiple sensory levels simultaneously, creating a cohesive and positive experience.

Of course, this technological transformation does not occur in a vacuum. Regulatory frameworks must evolve to ensure the safety and quality of these novel foods. Clear labeling is also paramount; while the goal is to make products appealing, transparency about ingredients builds trust. Furthermore, the entire supply chain—from insect farming (minilivestock) to processing and packaging—must be scaled up efficiently and sustainably to meet potential demand.

In conclusion, the mission to make insects a staple of the global diet is being fought on two fronts: the chemical and the physical. Through advanced flavor masking, we are learning to speak the language of the human palate, creating tastes that delight and satisfy. Through innovative morphological reconstruction, we are designing forms that comfort and feel familiar. Together, these technological pathways are not just disguising insects; they are transmuting them into a new, sustainable, and exciting category of food, poised to make a serious contribution to the future of our plates and our planet.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025